Editor’s Note: In this story, appraiser John Lifflander explains the roles played by the Feds, brokers/lenders and yes, appraisers, in getting us into the lending “meltdown.” The story is reprinted with permission from Fair and Equitable magazine, published by IAAO (International Association of Assessing Officers).

Rise and Fall of Real Estate Values

by John Lifflander, ASA

In September 2007, Alan Greenspan, former Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (the Fed), explained on The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer (September 18, 2007) that “we’ve had a bubble in housing.” He also spoke on the television show 60 Minutes with Lesley Stahl (September 13, 2007) in the wake of the subprime mortgage and credit crisis in 2007, saying, “I really didn’t get it until very late in 2005 and 2006.”

It is interesting that Greenspan did not “get it” because he essentially started it. He lowered rates and kept them down during President Clinton’s administration and continued to do so during the second Bush administration and that practice is a major reason for the current problems in the real estate market.

Greenspan was able to get away with the rate reductions because government indicators showed that inflation was under control. However, these indicators are skewed because the government measures only core inflation, which does not count food and energy cost increases, causing economists to say that “Core inflation makes sense only for people who don’t eat or drive” (Cooper 2007). It also ignores selected items for other reasons; for example, the increase in the cost of cars is not counted because it is claimed that cars are always improving.

Nevertheless, beginning in the 1990s there was a reason many manufactured items did not increase in cost: the influx of goods made in China. With the cheapest labor costs in the world, China began exporting items at prices well below those for anything manufactured in the United States. This forced many companies to either go out of business or make their products overseas. As a result, prices for many items went down, even if the cost of other items increased. The average, however, made it appear that inflation was relatively low.

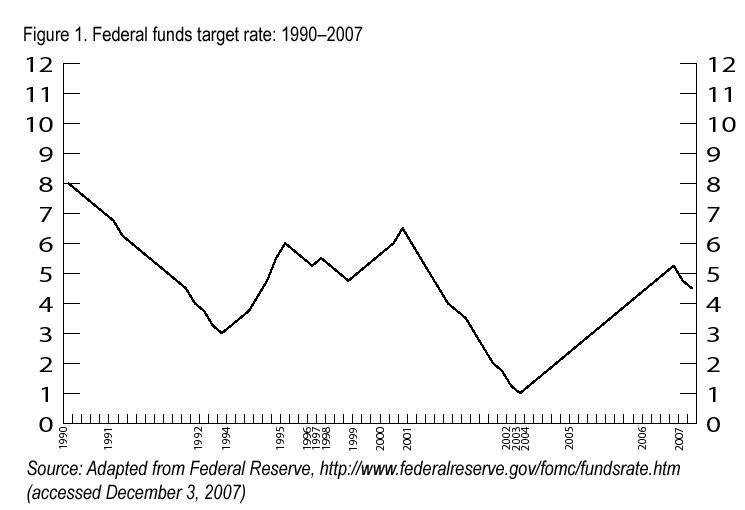

All these factors gave the government an excuse to keep rates down for a prolonged period of time and eventually housing prices started to escalate. Typically, when Americans want to buy a house, they look at the monthly payment that fits their income, not the price of the property. So if interest rates are lowered, prices are bound to eventually increase. Figure 1 and Table 1, based on data from the Fed, tell the story of how rates were changed. Figure 1 shows the rates since 1990. In 1994 and also during 1997 and 1998, rates were historically low, but they decreased to their lowest in more than 40 years in 2002–2004.

Table 1 shows the differences and the increases and decreases since 1990. Note how the rate in 1990 (eight percent) decreased steadily from that time forward.

…

| Date |

Change (basis points*) |

Level (percent) | Date |

Change (basis points*) |

Level (percent) | ||||||

| Increase | Decrease | Increase | Decrease | ||||||||

| 2007 | Sept.18 |

50 |

4.75 |

1998 | Nov.17

Oct 15 Sept.29 |

25 25 25 |

4.75 5.00 5.25 |

||||

| 2006 | Jun 29

May 10 Mar 28 Jan 31 |

25 25 25 25 |

5.25 5.00 4.75 4.50 |

1997 | Mar 25 |

25 |

5.50 |

||||

| 2005 | Dec 13

Nov 1 Sept 20 Aug 9 Jun 30 May 3 Mar 22 Feb 2 |

25 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 |

4.25 4.00 3.75 3.50 3.25 3.00 2.75 2.50 |

1996 | Jan 31 |

25 |

5.25 |

||||

| 2004 | Dec 14

Nov 10 Sept 21 Aug 10 Jun 30 |

25 25 25 25 25 |

2.25 2.00 1.75 1.50 1.25 |

1995 | Dec 19

July 6 Feb 1 |

50 |

25 25 |

5.50 5.75 6.00 |

|||

| 2003 | Jun 25 |

25 |

1.00 |

1994 | Nov 15

Aug 16 May 17 Apr 18 Mar 22 Feb 4 |

75 50 50 25 25 25 |

5.50 4.75 4.25 3.75 3.50 3.25 |

||||

| 2002 | Nov 6 |

50 |

1.25 |

1992 | Sept 4

July 2 Apr 9 |

25 50 25 |

3.00 3.25 3.75 |

||||

| 2001 | Dec 11

Nov 6 Oct 2 Sept 17 Aug 21 Jun 27 May 15 Apr 18 Mar 20 Jan 31 Jan 3 |

25 50 50 50 25 25 50 50 50 50 50 |

1.75 2.00 2.50 3.00 3.50 3.75 4.00 4.50 5.00 5.50 6.00 |

1991 | Dec 20

Dec 6 Nov 6 Oct 31 Sept 13 Aug 6 Apr 30 Mar 8 Feb 1 Jan 9 |

50 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 50 25 |

4.00 4.50 4.75 5.00 5.25 5.50 5.75 6.00 6.25 6.75 |

||||

| 2000 | May 16

Mar 21 Feb 2 |

50 25 25 |

6.50 6.00 5.75 |

1990 | Dec 18

Dec 7 Nov 13 Oct 29 July 13 |

25 25 25 25 25 |

7.00 7.25 7.50 7.75 8.00 |

||||

| 1999 | Nov 16

Aug 24 Jun 30 |

25 25 25 |

5.50 5.25 5.00 |

||||||||

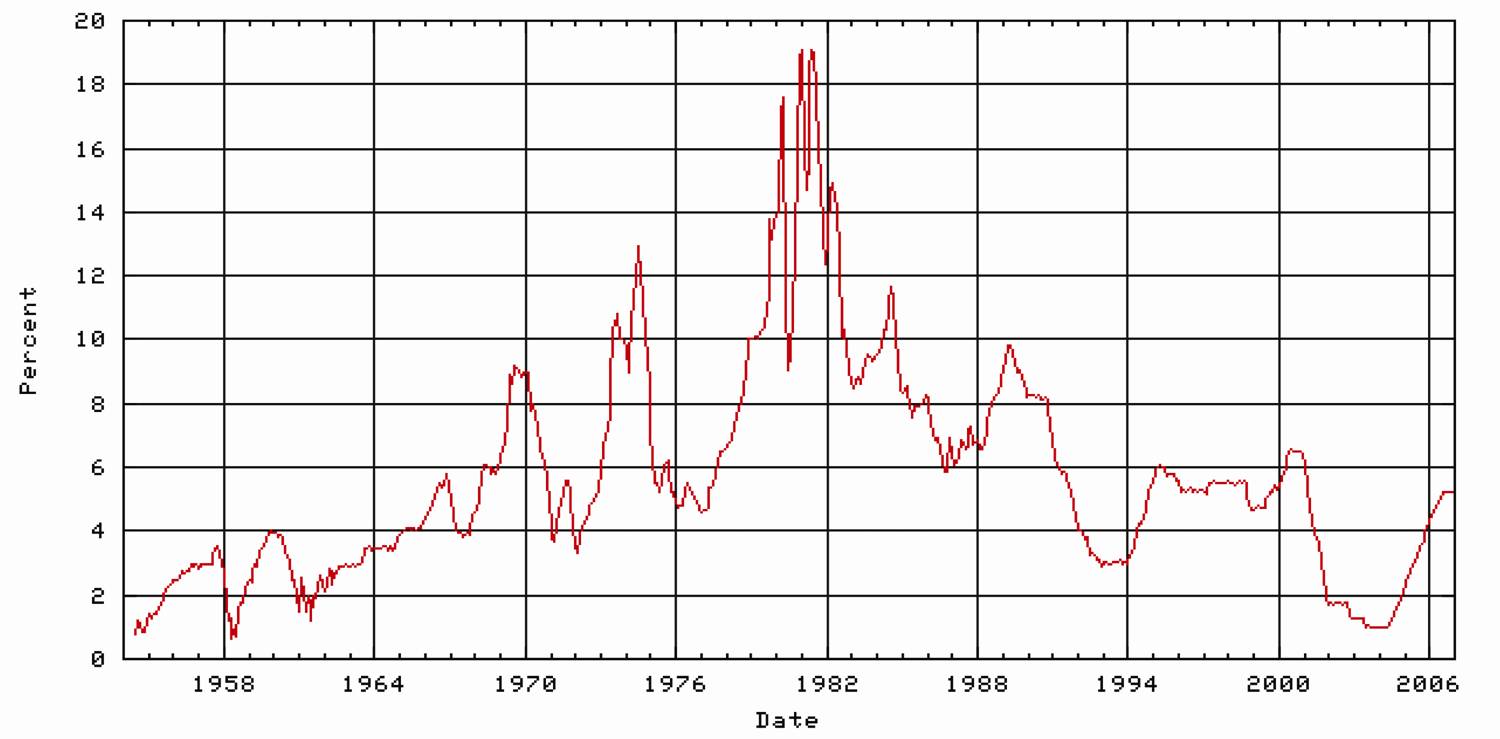

Figure 2 is an overview for the 52-year period from 1954 to 2006. Note that the rates are lower in recent years than in the preceding 40 years.

Certainly the argument could be made, as many have, that the Fed was acting irresponsibly. In the October 1, 2007 issue of BusinessWeek, Vitaliy Katsenelson, author and portfolio manager, speaking of the latest rate cut by the Fed said, “The 2001 rate cuts caused the bubble that is now a crisis. Indeed, at the core of today’s credit mess—whether in housing or the now battered markets for commercial paper—lies a glut of global liquidity. That has dramatically altered our perception of risk and fueled an unwillingness to accept traditional credit limits.”

This leads to the second factor causing these problems. Besides the fact that money became “cheap” when the Fed lowered rates, it also became more available because lending practices loosened. Irresponsible changes occurred, such as the Fed’s reserve requirements for banks, which were loosened in the late 1980s, allowing banks to keep a lower percentage of deposits and therefore lend a higher percentage of their funds.

Mortgage Lenders

As rates declined, mortgage lenders also loosened their requirements and invented new types of loans based on the fallacious supposition that people would be able to pay more in the future, since real estate and wages would continue to increase indefinitely. Many of these loans were given to people with good credit who wanted to buy more expensive homes than they could otherwise afford. With an adjustable rate mortgage starting at three percent, for example, the monthly payment on a $400,000 mortgage is only $1,686 per month, $712.00 less than the $2,398 required at a six percent rate. As Katsenelson goes on to say in the BusinessWeek article, “If a home owner couldn’t qualify for a conventional mortgage, brokers were more than happy to offer an exotic loan the borrower could never realistically pay off. If a loan was too risky to be sold as investment-grade, investment banks could always concoct elaborate bundles of good and toxic credits that (supposedly) eliminated risk.”

At the same time, the advent of subprime lending was perhaps the most serious development to lead to the present quagmire. One of the biggest players in that market was a company called Ameriquest, which targeted people with bad credit and made loans to them for exorbitant rates. In 2006, Ameriquest paid a record $325 million to settle a class-action lawsuit over allegations of predatory lending practices, such as bait and switch and usury. However, while Ameriquest was in its heyday, making millions of dollars with subprime loans, other lenders noticed and joined in. New companies were created only for this business and many of them are now defunct. General Electric got into the business with WMC Mortgage and “A” paper lenders such as Countrywide, the largest mortgage lender in the United States, joined in with its Full Spectrum branch.

Moreover, lenders like Washington Mutual, although they did not make subprime loans, were buying packages of subprime loans from lenders like Ameriquest. If the Fed had been irresponsible, the lenders compounded it by their shortsighted practices. They also forgot a basic rule in lending: that people with bad credit who do not pay their bills generally do not change. And adding to this mess is the fact that the loan broker rarely has a stake in what happens to the loan after it is made, since it is generally sold off to another entity.

Appraisers

After the real estate meltdown in the 1980s, the government decided that appraisers should be licensed. Licensing was supposed to protect the public from fraudulent loans because appraisers would be sufficiently educated in the profession. That would have been a grand solution if education was really the issue before licensing was required. However, the real problem was, and continues to be, the fact that lenders can hire their own appraisers. This practice immediately puts the appraiser in the position of having to please the lender to stay in business. This is akin to the proverbial fox guarding the henhouse but it has been ignored by the banking establishment.

In fact, in the 1980s HUD/FHA (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development/Federal Housing Administration) appraisers were assigned to cases just as VA (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs) appraisers are today. It was a random assignment system that precluded any involvement of the appraiser with the lender to procure the work. However, that practice stopped after the banking industry lobbied Congress to allow lenders to choose their own appraisers for FHA loans.

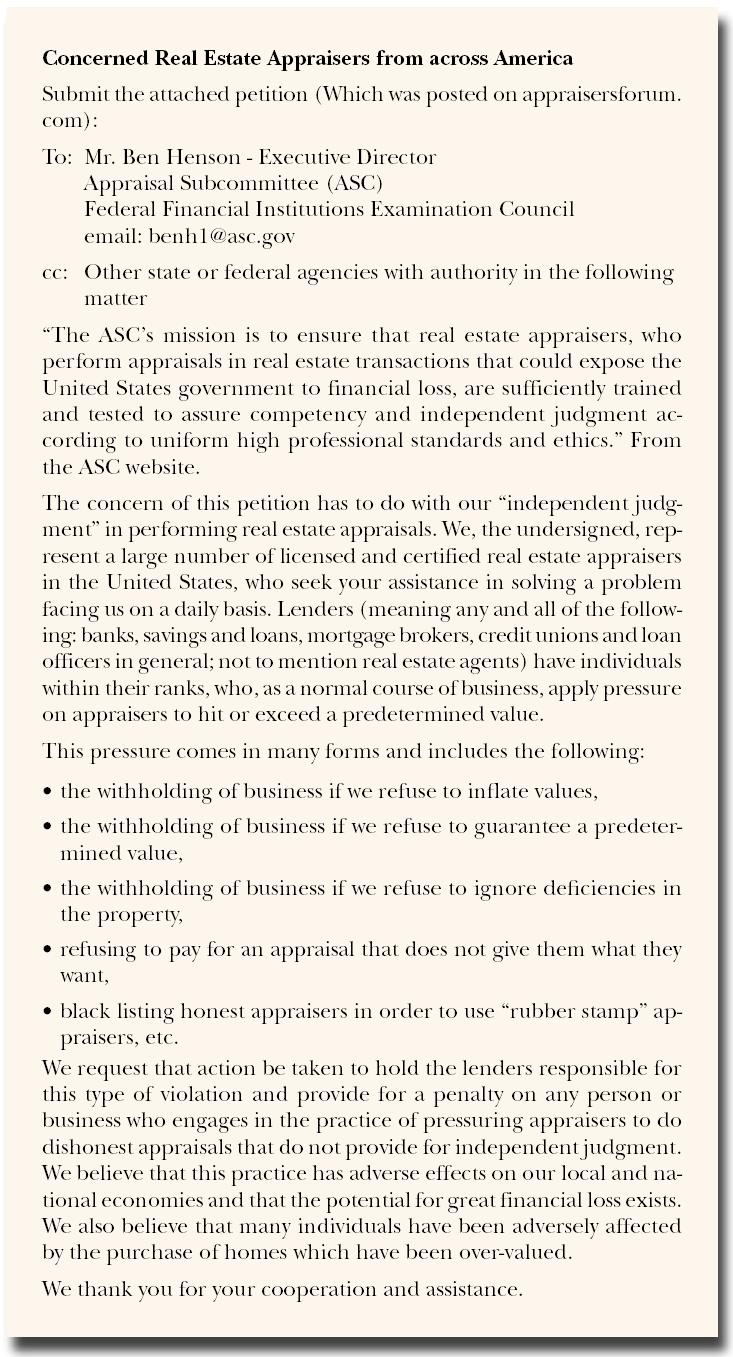

The pressure that appraisers face is tremendous and has resulted in a petition from “Concerned Real Estate Appraisers from across America” to the Executive Director of the Appraisal Subcommittee of the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council. Unfortunately, many appraisers give in to inflating values to keep working, which has added to the problems of the current real estate debacle. Appraisers find that even long-time clients do not call them back if they fail to “bring in the value” for even one transaction. Moreover, the appraiser is often labeled as a “bad” appraiser if the value is not as requested. This travesty has resulted in honest appraisers being punished by not getting work, and dishonest appraisers being rewarded with more work, even though they perform fraudulent appraisals.

Other Contributing Factors

Including owner concessions in the purchase money agreement is another factor that has inflated values. Once a rarity, it has become a common practice—probably because of the malleability of appraisers—for everyone to assume that the value will come in regardless of the padding of “thin air” to the sale price. For example, a buyer wants to make an offer that is $7,000 lower than the property’s listed price of $280,000. Instead of offering $273,000, the buyer offers the full price with concessions of $7,000. The concessions might be attributable to closing costs or to a rebate, but the effect is that the lender is financing a larger percentage of the market value of the property.

Concessions have a twofold effect on the market. First, as they have become common, they inflate values approximately two to three percent, depending on the amount. Second, when appraisers or buyers and sellers look at sales, many of the sale prices do not reflect the actual money paid for the house. Moreover, appraisers rarely know if there are concessions associated with the sale comparables they are using because they are not noted in most multiple listing services, and calling each party to the loan is too time consuming, and often agents are unwilling to cooperate.

Another reason for the decline in the current market situation in most areas is the fact that the majority of real estate investors have left the marketplace and instead are attempting to sell their properties. Many of those who invested in real estate in the past several years were previously in the stock market or had never invested before but wanted to “get in the game” because they saw large increases. Some first-time investors used equity lines on their homes to make the down payments for their purchases. These “amateurs” often paid more for homes than savvy real estate investors normally do, driving prices sky-high. It is estimated that the amount of real estate purchases for single-family residences bought by investors is between 10 and 25 percent, depending on the region of the country. With these people no longer buying and with some selling, inventory is increasing and prices are decreasing.

In the multifamily residence market, capitalization rates have descended over the past several years. This drop is related to lower interest rates and optimistic over speculation. The lower the capitalization rate, the higher the value. And in many areas of the country capitalization rates decreased substantially as interest on FDIC-insured certificates of deposit (CDs) decreased because of the decrease in the Fed’s prime rate, which also decreased mortgage costs.

Investors who had previously kept their funds in CDs and other interest-bearing financial instruments became disenchanted as the rates subsided. The alternative of real estate investments became more palatable—although the capitalization rates may have sunk to five–six percent, they were still higher than or as high as CD rates and real estate values were increasing quickly. Income-producing property was also increasing in value faster than many stocks, so many stock market speculators switched to real estate as well.

The Resulting Ad Valorem Problems

Essentially what has occurred, at least in many parts of the United States, is an increase in values not driven by solid real estate economics but by unrealistic speculation, loose lending practices, fraudulent appraisals, and cheap money. These factors fueled an inflated bubble in prices and assessors around the country have found it difficult to keep up with the drastic increases in real estate values. Those jurisdictions that are under a mandate to revalue annually have been particularly affected. The job of keeping up is further complicated by the fact that the application of increases often lags the market by at least a year. In other words, market values may have increased for the time period under assessment and then decreased afterwards, making the increased property tax bill appear inaccurate because the current market had decreased in the meantime.

One solution for the future would be to develop an awareness that drastic increases may constitute a market swing and it may not be worth increasing assessments until the market stabilizes. The problem with implementing this policy could be the legal mandate for many assessors that that they value property as of a certain assessment date. In any event, one way of ameliorating the backlash for increased assessments that now appear untimely is for assessors to make a special effort to educate property owners. Assessment offices need to be very clear about the date for which the assessment has been made and also to explain that reductions, if warranted, will occur the following year and go down as quickly as they increased.

About the Author

John Lifflander, ASA, is a Certified General Appraiser in Washington and Oregon, and is president of Covenant Consultants, Inc., an appraisal and property tax consulting firm. He teaches appraisal courses and has been published numerous times, and is the author of Fundamentals of Industrial Valuation, a textbook for industrial appraisers published by IAAO (International Association of Assessing Officers). He is a former administrative law judge for property tax appeals for the Oregon Department of Revenue and specializes in providing expert witness testimony and consultation for complex valuation litigation. He can be reached at john@liffland.com.