|

> E&O Insurance: Broad Coverage, Low Rates, Instant Quoting > InspectorAdvisor: Get Your Tough Inspection Questions Answered by a Pro |

The following is reprinted from Working RE Inspector, a nationwide print magazine exclusively for home inspectors. If you are not a subscriber, you can read the entire magazine here.

Dew Point – The Mysterious Mix of Water and Temperature

By Tom Feiza, Mr. Fix-It, Inc.

Dew point affects many home issues and mechanical systems. Basic principles of science explain how dew point works and how this relates to home inspections.

Dew Point Basics

Invisible water vapor is always present in the air. At times, it condenses as visible moisture. Dew point is expressed as a certain temperature. Outdoors, when the air temperature drops below the dew point, condensation occurs, causing rain to fall—for example, it rains when a cold front moves in.

You can also see dew point at work on a hard surface, such as the outside of a glass of water. If the temperature of the drinking glass is below the dew point of the air around it, water condenses on the outer surface of the glass. When you see moisture forming on a surface, think: “The temperature of the surface is below the dew point temperature of the air.” That’s all you need to remember.

But what does dew point mean to home inspectors? Here are some situations you’re likely to encounter.

Window Condensation in Cold Climates

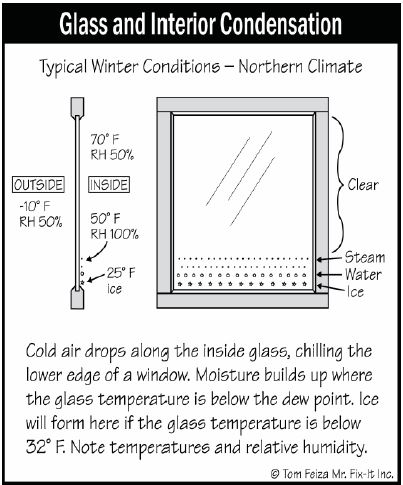

Dew point is at work when condensation occurs on cold windows (See Figure 1).

Figure 1

During the winter, window glass is often the coldest surface in the home. Cold air drops along the glass to the sill. The glass stays even colder when an interior screen or shade keeps radiant heat in the room from reaching the glass. The temperature of the glass is below the dew point temperature of interior air, so condensation forms. If the glass is colder than 32 degrees Fahrenheit (F), ice will form (See Figure 2).

Figure 2

What should you tell customers with window condensation problems? “The temperature of the glass is below the dew point temperature.” There are two ways to remedy this: either raise the temperature of the glass or reduce the moisture in the air. Glass temperature increases along with higher outdoor temperature, higher indoor temperature, open shades, or even indoor air movement. Set up a small fan to blow air on the problem window; the moisture will go away, because air movement raises the temperature of the glass.

Condensation in Hot, Humid Climates

In hot, humid climates, condensation forms on the outside of windows (See Figure 3).

Figure 3

The home’s air conditioning cools the window. The cooling effect eventually reaches the outside of the glass, and when it drops below the dew point temperature of the air, condensation occurs on the outside.

Exterior glass condensation can also occur in cold climates when air conditioning is running and the air is hot and humid. If the air cools overnight and drops below the dew point temperature of the glass, condensation occurs.

Dew Point and Central Air Conditioning

You already know that air conditioning lowers indoor air temperature and removes moisture, which drains away from the air conditioner through a condensate (water) drain line. This process, too, involves dew point. The evaporator coil remains at about 45 degrees F. A fan blows home air across the coil, and since the coil is below the dew point temperature, the air is cooled and moisture forms on the cold coil.

(story continues below)

(story continues)

100 Degrees in Arizona – but It’s Dry Heat

Why do we feel cooler when air is dry? Because the dew point temperature is low. Dry air allows water to evaporate from our skin as invisible vapor at a faster rate. The dry air is looking for water.

When water evaporates from our skin, it changes phase from bulk water to vapor. Our warm body transfers heat to the water so it can evaporate (boil). As the change of phase takes place (boiling), the body is cooled. It takes 144 BTU of energy for each pound of water evaporating from our skin.

You can test this yourself by jumping into a pool. When you get out, you will feel colder as the moisture on your skin evaporates into invisible water vapor in the air. More wind or other air movement causes more evaporation.

Wind Chill Effect

Let’s say you live in a cold climate. What is that “wind chill” the weather person talks about? On a windy day, the wind chill temperature is below the air temperature. That’s because when skin is subjected to air movement, we feel cooler. The water on our skin evaporates (boils) into invisible water vapor, and heat transfers from the body to evaporate water at a faster rate. Wind also breaks through the thin layer of warm air surrounding the skin, increasing the rate of convection away from skin.

Heat Index

OK, let’s boil that water from our skin again – remember it takes energy for the change of phase from water to vapor. When the air is hot and humid, the dew point is high. The moisture on our skin evaporates at a slower rate because the air is already saturated with water. When less water evaporates from our skin, we feel warmer.

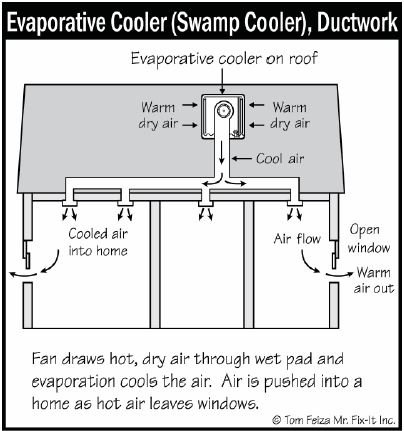

Swamp/Evaporative Coolers

In hot, dry, desert-like climates, it makes sense to cool homes with swamp coolers or evaporative coolers. A typical swamp cooler sits on the roof, with ductwork connecting it to the home’s interior (See Figure 4).

Figure 4

The swamp cooler itself contains evaporative material saturated with water. A fan draws in dry, hot outdoor air and moves it across the material. The water on the material evaporates (boils) into invisible water vapor and heat is removed from the air. The system needs a water supply. A small pump constantly floods water into a pan holding the evaporative medium. These units do add moisture and raise the dew point temperature of the air, but since the air was desert-dry before it entered the system, adding a little moisture doesn’t make the home’s interior uncomfortable. The system requires constant maintenance, because circulating outdoor air draws dirt into the evaporative medium and the water.

Old, Dry and Drafty Homes

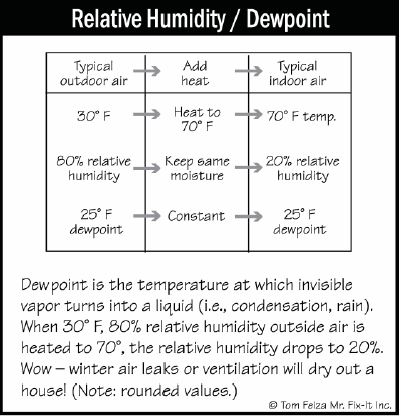

Imagine a drafty old house during a cold winter. Air leaking in from outdoors makes the interior of this house cool and dry – and kids have great fun shuffling their feet on the rug to create shocks from static electricity. Figure 5 shows that when we take typical outdoor air at 30 degrees F and 80% relative humidity and heat it to 70 degrees F indoors, the relative humidity drops to 20% but the dew point stays at 25 degrees F (See Figure 5).

Figure 5

That cold outdoor air really dries out a home as it moves indoors. It doesn’t cause condensation on interior surfaces because the indoor temperature is above the dew point of 25 F.

Dripping Bath Fan in Cold Climate

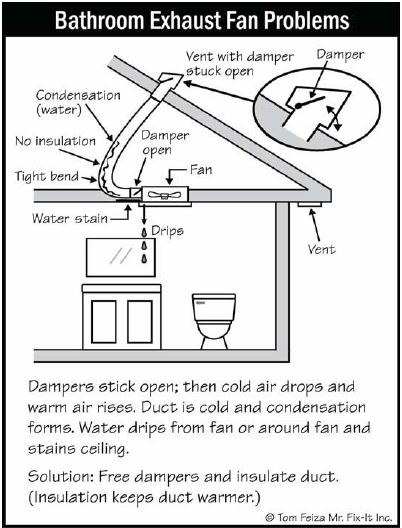

Another situation you might encounter: water dripping around the housing or below the discharge duct of a bath fan (See Figure 6).

Figure 6

Attic Mold in Cold Climate

If there’s mold on the roof deck, it must be below the dew point temperature, right? Water is essential to mold growth. Mold occurs on the roof structure and deck in a cold climate because the framing and deck have been wet over time. Warm, moist interior air is leaking into the attic through gaps around light fixtures, plumbing and electrical penetrations and around the chimney. As the warm, moist air contacts the cold roof deck, it is cooled below the dew point temperature. Water forms and mold grows on the attic dirt and wood. The solution involves stopping those air leaks. Installing air seals between the heated space and the attic will address this problem.

Always remember the answer to condensation questions: “The surface temperature is below the dew point temperature.” And remember the solution: raise the surface temperature or lower the moisture level in the air around the cool surface.

>> Visit HowToOperateYourHome.com for high-quality marketing materials that help professional home inspectors boost their business.

About the Author

Tom Feiza has been a professional home inspector since 1992 and has a degree in engineering. Through HowToOperateYourHome.com, he provides high-quality marketing materials that help professional home inspectors boost their business. Copyright © 2015 by Tom Feiza, Mr. Fix-It, Inc. Reproduced with permission. Visit HowToOperateYourHome.com or www.htoyh.com for more information about building science, books, articles, marketing, and illustrations for home inspectors. Please e-mail Tom (Tom@ misterfix-it.com) with questions and comments. Phone: 262-303-4884

> Free Webinar: Claims and Complaints: How to Stay Out of Trouble

Available Now

Presenter: David Brauner, Senior Insurance Broker OREP

David Brauner, Senior Broker at OREP, shares insights and advice gained over 20+ years of providing E&O insurance for inspectors, showing you how to protect yourself and your business. Watch Now!

by Rebecca Gardner

It was interesting when you talked about how water vapor is always present in the air, but it doesn’t become visible until after the condensation process transforms it into a liquid. Now that I think about it, I’m curious if condensation could be controlled and used to harvest the ever-present water vapor directly from the air. I enjoyed reading your article and learning more about the details of dew point and condensation, so thanks for taking the time to share!

-